Physiology Matters: A deeper look at the physiological roots of today’s aesthetic sameness

- Nicole Cutler

- Dec 8, 2025

- 3 min read

We speak endlessly about technique, shaping, speed, and style, yet far less about the body that carries it. And the body is not neutral. Physiology matters.

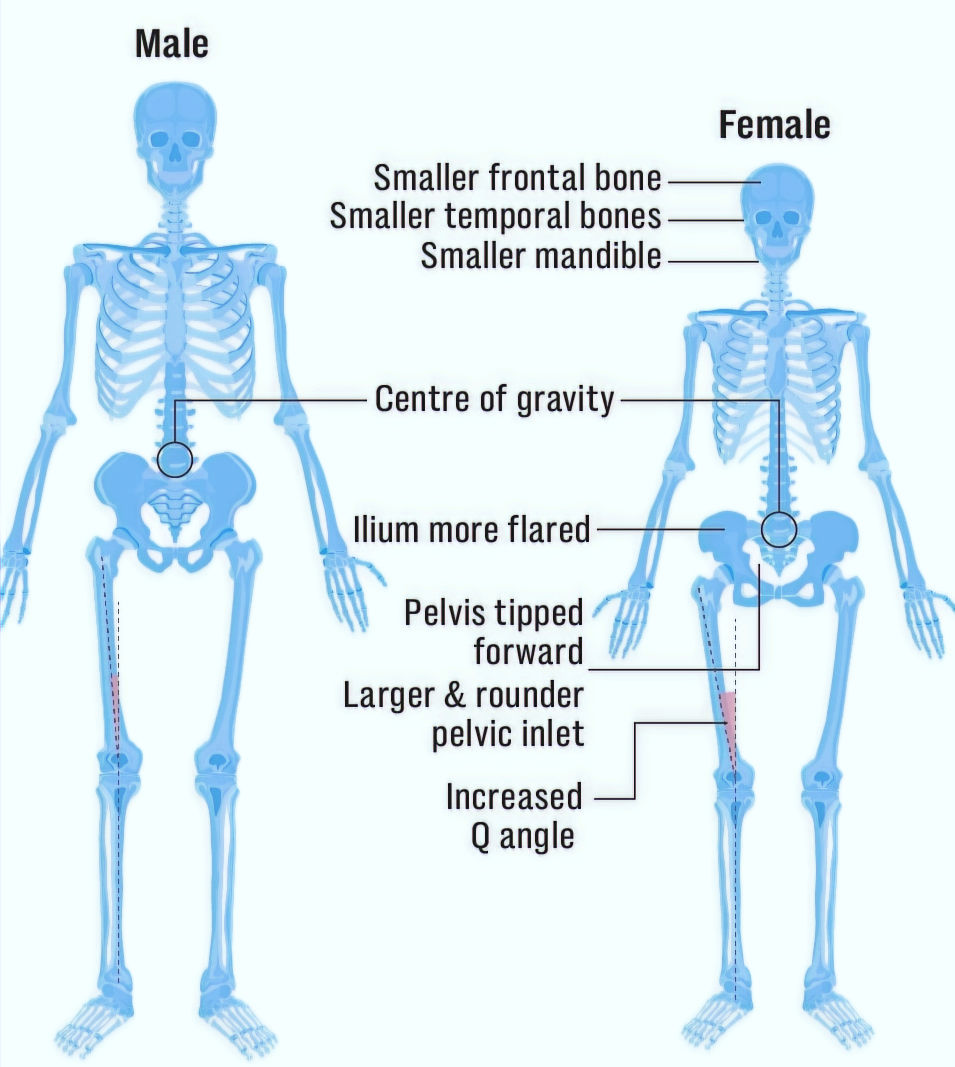

The architecture of the male body and the female body is not the same. Their centres of balance differ. Their pelvic structures organise weight and rhythm differently. The pathways through which power travels vary. Even the mechanics that drive rotation operate through distinct patterns of leverage and stability. These are not aesthetic preferences. They are physiological truths recognised across sport science and biomechanics.

These differences shape how movement feels and what comes naturally. They shape possibilities and constraints. Neither set of patterns is better or worse. They simply form the physical vocabulary through which movement is organised from the inside out. When dancers work with the physiological design of their own body, they often find clarity and ease. When they are asked to work against these patterns, movement can become tense or effortful, or expand into shapes the body cannot sustain long term.

This is where our current Dancesport landscape meets a quiet dilemma. Many of the qualities that dominate the aesthetic today, such as extreme speed, high torque rotation, sharp directional changes, and power initiated high in the torso, sit more comfortably within the mechanical structure of the male body. Broader shoulders, narrower hips, and a centre of mass carried slightly higher allow these actions to be produced with relative efficiency.

Female dancers can and do achieve the same outward results. They do so with extraordinary skill. Yet they often reorganise internal movement pathways more extensively to reach the same visual effect. Their wider pelvis, lower centre of mass, and different mechanisms for generating force mean that identical shapes do not arise through identical physical routes.

None of this diminishes artistic capacity. It simply acknowledges that one aesthetic may stand closer to one set of mechanics than another.

This is not a criticism. It is an invitation to notice what has long gone unspoken. When choreography or technique is built around movement strategies that sit naturally in one type of body, dancers with different structures may find themselves adapting more, compensating more, or sensing that what comes easily to them is somehow “less”.

The issue is not the movement itself. The issue is the assumption that every body will experience that movement in the same way.

As aesthetic trends narrow and global training systems promote increasingly uniform outcomes, the physiology of the dancer is often treated as an obstacle to be corrected rather than a source of intelligence. Technique and choreography frequently assume that all bodies should move in the same way, with the same structures, speeds, and power lines. In this environment, it is often female dancers who adapt the most, reshaping their natural movement pathways to match a standard built around different mechanics.

Some dancers manage this adaptation with remarkable determination. Others find themselves pushing against their own design, sensing that something is misaligned but unable to articulate why. And many begin to question the worth of the qualities that arise naturally in their body simply because those qualities are no longer prioritised in the current aesthetic.

This raises an essential question. Can any of us fully understand what movement feels like inside a body that is not our own? Not through projection or mimicry, but in its physiological truth. Coaches cannot fully feel what a dancer feels, just as dancers cannot fully feel what their teachers feel. When a teacher guides a body built differently from their own, the gap widens further.

Understanding physiology is not about dividing dancers. It is about recognising that every dancer carries a unique architecture. Teaching that overlooks this reality inevitably narrows expressive possibilities.

If physiology returns to the centre of teaching and choreography, the landscape begins to shift. Technique becomes a language that adapts to the dancer rather than a mould imposed upon them. Choreography becomes a conversation with the dancer’s structure rather than a test of what the body can withstand.

And individuality, which can sometimes quieten in environments shaped by strong global trends, has the chance to breathe again.

The deeper question is not who can match a trend or fit a style. The question is how many natural styles we overlook when we forget how each body is built to move. When physiology re-enters the conversation, dancers stop chasing an ideal that was never designed for them and start discovering the artistry that only their body can produce.

Physiology is not a limitation. It is the beginning of possibility.

Comments